A film movement can be defined as a wave of films that tend to follow a particular trend or a common set of stylistic trademarks reflective of their time. While the origins of most movements have been regional, their impact has been global. Having been shaped by people, culture, and social norms, film movements are a great way to reflect upon a culture and a particular time frame.

Along with cultural influences, filmmaking techniques can also be used to create a canvas for a film movement, resulting in an experimental approach to cinema and storytelling. Looking back, a lot of modern-day filmmakers consult and revisit many film movement masterpieces for reference and inspiration, making them an active part of cinema’s history and a vital part of its future. Here are 10 of the most important film movements that defined cinema forever.

Poetic Realism

Poetic Realism originated in France in the '30s and was rich with themes of nostalgia, with a focus on unrequited love. Poetic Realism is also known to have influenced the Italian Neorealism movement and the French New Wave, as filmmaking started gravitating towards themes of naturalism. Jean Renoir (who was also associated with Surrealism) was a prominent figure in the movement, notable for films like The Grand Illusion and Les Bas-fonds.

Nuevo Cine Mexicano

Having originated in the early '90s, New Mexican Cinema is an ongoing wave that diverted the attention from Narco-culture and, instead, took inspiration from European and American films. Without the overt use and reference of cartels and drug culture, the films of the Nuevo Cine Mexicano revolve around a flare of Mexican culture, realism, and romance. The major figures of this movement are Alejandro González Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón, and Guillermo del Toro, with films like Amores Perros, Y Tu Mama Tambien and The Devil’s Backbone being some of the movements' more notable works.

Dogme 95

Dogme 95 crudely translates to Dogma, as in a set of principles, and 95, the year it was created. Having been pioneered by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, Dogme 95 is one of the few movements that operate on a set of official rules documented in a manifesto. A few hardcore rules of the genre include that films must only be shot using 35 mm film (which was later changed to videotape), films were to be shot on handheld cameras without filters and the films were only to be shot on location, lending the movement a very documentary feel to it.

German Expressionism

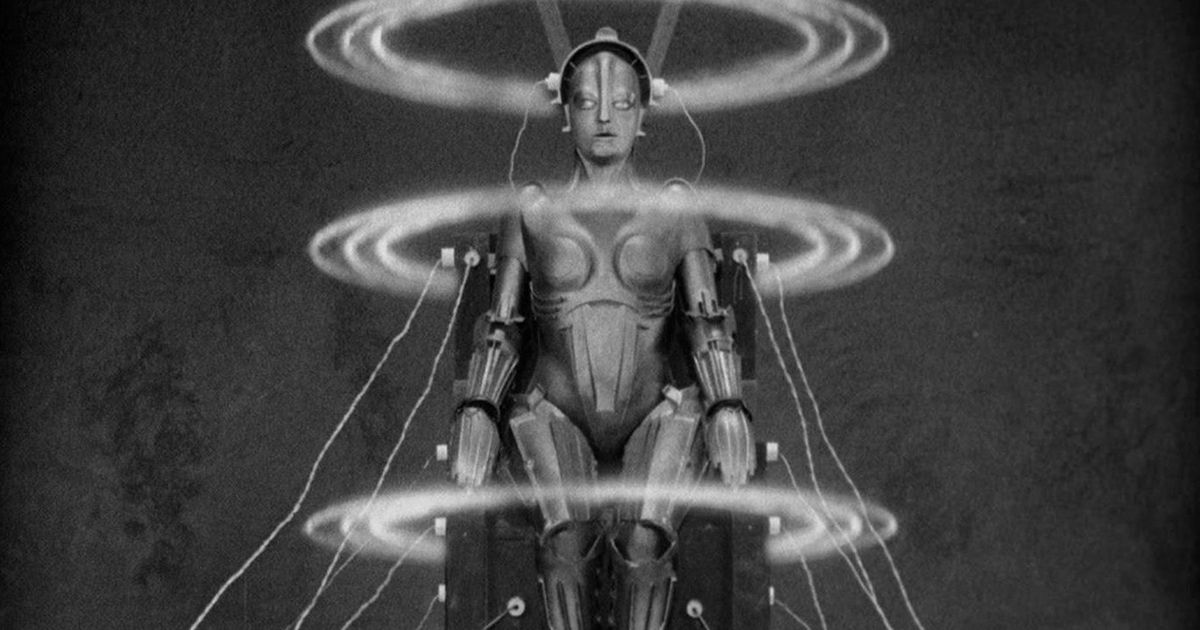

During WWI, in an attempt to isolate Germany from Western influence, the government banned foreign films, creating a need for German film production. This unwittingly gave birth to an avant-garde film movement known as German Expressionism, as the entire economy was low on income and high on ideas.

Scrapped for cash and resources, filmmakers of the time made the most of art design, the interplay of light and shadows, and a splash of yellow color to give the scene a different mood. As the Nazis came into power, they deemed the movement unworthy, forcing legendary filmmakers like Fritz Lang (Metropolis) and F.W Murnau (Nosferatu) to flee to Hollywood.

Surrealism

Having originated in Paris in the 1920s, Surrealism aimed at challenging traditional art forms by using absurd and shocking imagery. Jean Renoir, who was also a prominent figure in the Poetic Realism movement, pioneered the movement with films such as La Fille de L’eau along with painter Marcel Duchamp (under the pseudonym Rose Sélavy).

Parallel Cinema

Currently, India has the largest film industry in the world. Despite not being on par with Hollywood in terms of technical prowess, Indian films have evolved manifold over time. The sensibilities attached to conventional Bollywood are creatively constipated while suffering from a severe diuretic bout of meritocracy.

Current cultural catastrophe aside, this wasn't always the case. Indian cinema had a rich and cultured beginning with films such as Neecha Nagar (only Indian film to ever be awarded the Palme d’Or) and Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali. Bengali filmmakers took inspiration from European cinema and stepped away from the song and dance of Bollywood and displayed India’s true cinematic prowess to the world.

Iranian New Wave

Made with censorship in mind, Iranian films are extremely unique and different. There are many do's and don’t's attached to the censorship of these films, as filmmakers have to submit their scripts to the government before they’re allowed to begin filmmaking.

Having taking inspiration from neo realism (documentaries), Iranian filmmakers use filmmaking to explore and document the fabric of their society. Some key figures of the movement like Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi slowly turned into filmmakers of global repute, having regularly been spotted at Cannes and Sundance.

New Hollywood

Also known as American New Wave, this movement saw a shift in power dynamics, where the studios transferred the reigns over to the director. Pioneered by raw and gritty films like Taxi Driver, Easy Rider,and The Graduate, New American Wave filmmakers avoided traditional movie making styles by creating stories without clear resolutions or classic narrative structure.

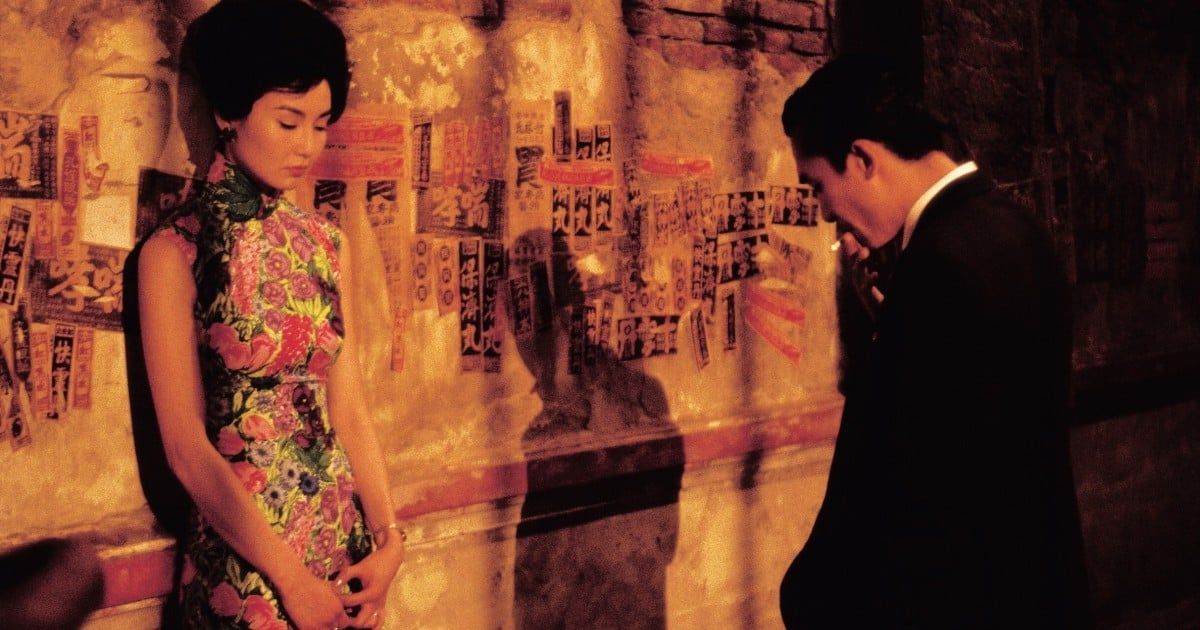

Hong Kong New Wave

Abandoning Mandarin Chinese, a few Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong-based filmmakers decided to step away from mainstream cinema. Having studied European films, these filmmakers went on to depict Hong Kong’s culture, pushing for their own national and cinematic identity. The movement also had a diversity in genres, with the likes of Wong Kar Wai propagating romantic films, whereas John Woo focused on cops and crooks.

French New Wave

Having originated in the '50s with the aim of changing cinema, French New Wave films had low budgets, but were stylish with a lot of tracking shots, quick pans, and handheld camera work, along with the famous jump cut.

The movement broke most conventional rules that worked on formulaic norms and infused a burst of energy and life into its films. Iconic directors like Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, and Eric Rohmer were pioneers of this movement, gifting us classics like The 400 Blows, Breathless,and Jules and Jim for generations to come.

Comments

Post a Comment